Paulo Freire through the eyes of Nita Freire: a 100-year struggle for equality and literacy

(by Filipe Albessu Narciso | reviewed by Kiara Neves) – December 20th, 2021

To commemorate the centenary of Paulo Freire’s birth, one of the paramount philosophers and educators of the 20th Century, we talked with Freire’s widow, Ana Maria Freire, about his life, values and immense impact on the world today. Ranging from the passion he had for his work and the adversities he faced during his lifetime to the legacy he established in contemporary education, Ana Maria Freire, commonly addressed by her nickname Nita, revealed a personality filled with an innate drive to promote equality and to fight for every person’s right to a voice of their own. Read more about Freire and our interview here.

Paulo and Nita Freire – Source: Benedito Leite Library.

Born in the Northeast Region of Brazil, in a city called Recife, on September 19th 1921, Paulo Freire was one of Brazil’s most remarkable educators and philosophers. Dedicated to a life of pursuing methods of inclusive and democratically driven education and literacy, Freire is reputed to be a highly influential name in the history of social sciences and is extremely relevant to the critical pedagogy movement. In Brazil, he is recognized as education’s patron saint.

In 2021, the world celebrates a hundred years of Freire’s history. He passed away in 1997, at 75, leaving behind a life work that is as relevant today as ever. His most famous book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, was released in 1968 and translated into English for the first time in 1970. Since then, it has sold more than 750,000 copies worldwide and is the third most cited book in social sciences.

His second wife and legal successor Nita Freire has also dedicated her life to education: she has a PhD and a master’s degree on the subject — and Freire himself was her mentor on the latter. In an interview in Portuguese, Nita expresses her tenderness and admiration for the educator in each and every answer.

A look into Freire’s history against social inequality

Paulo Freire’s vast intellectual production is deeply rooted in his observations as a member of the Brazilian lower middle class. From a very young age, everywhere Freire witnessed the harassment and marginalization of illiterate people and questioned what could be done to change those circumstances.

He enrolled in the Law School of Recife in 1944, this being his only course option for pursuing a career in the humanities at the time. “Paulo asked himself why the Northeast Region had so many illiterate people” — explains Nita Freire, gently addressing him by his first name during the entire interview — “he decided to dedicate himself to education because people were marginalized from society if they didn’t know how to write or read”.

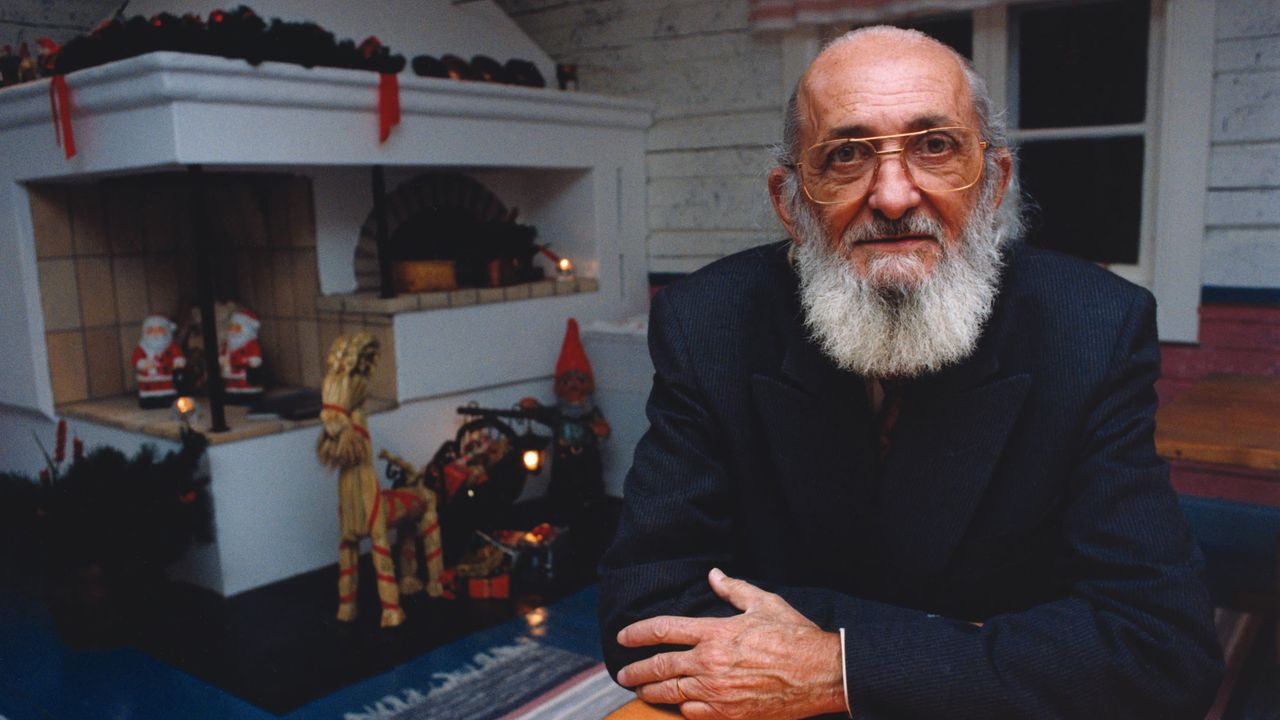

Paulo Freire – Source: Diário do Nordeste Journal.

Nita Freire was an important figure from early on in Freire’s life: Nita’s father was a principal who offered Freire a high school scholarship, consequently providing him with a chance to devote himself to his education. Back then, Freire’s family was going through the hardship of a declining social status and the recent passing of his father. Freire then noticed how hunger disrupted a person’s ability to learn as he witnessed the inequalities that affected his nation: in the 30’s and 40’s, about half of the Brazilian population were illiterate and consequently disenfranchised.

After working as a teacher for a couple of years and getting married to his first wife, Elza Maia Costa de Oliveira, with whom he would have five children, Freire was appointed director of his homestate Pernambuco’s Department of Education and Culture in 1946. In 1961, Freire was then appointed director of the Department of Cultural Extension at Recife University, which a year later led him to implement a project that helped 300 sugarcane harvesters learn how to read and write in just 45 days. The program was a success and demonstrated Freire’s abilities to guide Brazil into a more lettered and inclusive future.

However, two years later, a military coup would overthrow Brazilian president João Goulart and interrupt the educator’s plan, sending him to exile for several years. Nita reinforces that, in those trying times, Freire depended on receiving a safe-conduct from countries that would welcome him, because he wasn’t even able to obtain a passport. “He [Freire] had a mass literacy plan for Brazil back when Goulart was president. Then, the military and foreign businessmen decided it was a bad idea for Brazilians to able to read and write” reveals Nita Freire, “but, when a person has a desire, political will, intellectual capability, and they love their people, they don’t give up only because they’ve been told to do so”.

“It has been 24 years since Paulo died and the things he said and wrote are still being debated, used, and transformed into acts of grandness for our people”, Nita Freire points out.

During his exile, travelling back and forth to countries in America, Africa and Europe, Freire wrote Pedagogy of the Oppressed and experienced far greater international influence of his work. “He kept resisting and resisting, even out there Paulo didn’t give up on his purpose”, emphasizes Nita Freire, “he spent more than 15 years travelling from one place to another without being able to return to his homeland”.

In 1979, Freire was finally allowed to visit Brazil, and moved back in the subsequent year. He then joined the Workers’ Party (PT) and became the supervisor of their adult literacy project from 1980 to 1986. In 1988, Freire and Nita got married and, in the same year, when the candidate for the Workers’ Party in the São Paulo mayoral election, Luiza Erundina, was elected, he was appointed as the city’s Secretary of Education.

Nine years later, Paulo Freire would pass away as a result of a heart failure. Today, the world celebrates the educator’s posthumous hundredth birthday. Nita, who is now 88 years old, has published many works of the pedagogist, including a biography. “It has been 24 years since Paulo died and the things he said and wrote are still being debated, used, and transformed into acts of grandness for our people”, she points out.

Paulo Freire: a guiding light towards an inclusive future

Nita Freire – Source: O Globo Journal.

This year, for the first time since the foundation of the University of São Paulo (USP) in 1934, the amount of public school students enrolling at USP has surpassed the number of students that come from private institutions. This change is due to a series of inclusive policies adopted by the university, especially the social quotas implemented for its qualification process.

When given this information, Nita reinforced the institution’s responsibility to promote democratic principles and recalled how the word “university” already points out that it should be universal: a place for everyone where everything is studied. “It is essential to promote a better understanding of what a public university really is”.

Despite improvements in recent years, Brazil still has a long way to go when it comes to quality education. According to data gathered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Brazil comes in the lowest positions at most criteria related to education. Specifically regarding higher education, around 21% of the country’s young adults have a degree, while the average rate of OECD members is 44%.

Nita points out that education plays a major role in enabling individuals to have autonomy and, consequently, promote a democratic, inclusive society. “Paulo’s greatest desire was that people were inserted into society, leaving this ‘voiceless state’. As he used to say, ‘illiterate people are silenced, they cannot speak’”. Today, the percentage of illiterate people in Brazil is around 5% of the population. Freire’s work emphasized the importance of quality basic education for everyone, basing itself upon the concept of social justice. “What social justice asks, and let’s say even imposes, is that we all become acting subjects of history”, clarifies Nita Freire.

The educator’s widow admits being impressed by the substantial recognition that Freire receives up to this day. “Have you seen someone turn a hundred years old and receive so many celebrations and tributes? I haven’t”. However, Freire still isn’t liberated from conservative and reactionary groups who attempt to minimize his impact. “There are, let’s say, ulterior motives, depriving Paulo of his stature. Not only his stature, but the things that he was able to do and he is still able to do while deceased”. She then pointed out a recent setback on the country’s social progress, exemplifying with the attacks against native people and the wildfires in the Amazon Rainforest and other Brazilian biomes.

Yet, Nita Freire still keeps an optimistic attitude when it comes to education: “I believe that the tendency is that, within a few years, education and its policies — in cities, neighborhoods, states and the nation as a whole — will be aligned with freirean principles, because we need social justice, we need a society where everyone is able to learn what they want to learn”.